On my most recent post, I wrote a little bit about my time travelling in Georgia. Not the U.S. state, but the country. The first question people always ask me about Georgia is this: “Is that in Europe?”

Instead of a simple yes or no, my answer often seems to snowball into a longer conversation that usually goes like this:

Me: At the moment, it’s considered Eurasia. But they’re petitioning to be completely accepted as a European country.

Them: Huh? So it’s not in Europe?

Me: Well, I believe it’s both in Europe and in Asia. It’s at the intersection.

Them: Is it like Europe though?

Me: The city definitely has strong European vibes, but in some parts, especially those near Armenia, the Asian influences stand out more.

Why am I telling you this? It’s because I’m laying the foundation for this piece’s main metaphor. So, keep this anecdote in mind.

Act I

I was born, raised, and still reside in the Philippines—a cluster of islands located in Southeast Asia. You might miss us on a map if you’re not specifically looking for us or if you’re not a fan of beauty pageants or boxing.

When I was in elementary school, I learned that I was a third-world citizen because the Philippines has third-world problems, and that most of the first-world folks with first-world problems are in the West. As I write this, I am informed that “third-world” is no longer a term I am supposed to use, and that I should go for “developing” country instead. That sounds better, I guess. We are trying, we’re just not there yet. A work in progress, if you will.

Thoughts from the ER was the original title of this essay, because these feelings first bubbled up one recent Friday night when I found myself in the emergency room of a nearby private hospital after an insect tried to end me with one nasty bite on my arm. It all turned out okay…that is, after a 20,000 peso (approx. 360 USD) hospital bill. Thankfully, the insurance provider I pay annually for about the same price covered most of it, and I only paid around 3,000 pesos (approx. 52 USD) that night, which included a week’s worth of medicines my doctor prescribed.

I’m talking about money now because, during my six hours in the ER, feeling a little nauseous from the shot they gave me, all I could think about was: What about the people who can’t afford this? And I’ve lived long enough to know that there are many who can’t afford not just health insurance or hospitalization, but also medicines.

In fact, there was one person beside me at that moment.

I didn’t see her because we were separated by thin curtains, but from what I could gather, she was an elderly woman, about eighty years old, accompanied by three of her children. She needed some tests done and also needed to be placed in the ICU. I swear, I didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but it was a relatively quiet ER and they were only three steps to my left. They kind of had to shout too because the patient could no longer hear well.

Anyway, the family was informing the doctor that they couldn’t afford the tests or the ICU room and were asking if they could instead write a promissory note—essentially, a promise to settle the bill at a later date. For my non-Filipino readers, this is quite a common request, as “payment first” is the rule for most of the hospitals here. Unfortunately, it was out of the doctor’s hands it seemed, and the family had to sign a waiver stating that they were going home against the doctor’s advice.

Now, you might be thinking, Well, couldn’t they have just gone to a public hospital? They could have, that’s true; we do have those here. But here’s how a public hospital in a third-world developing country works: doctors’ fees and beds (if you’re lucky enough to be provided one, or allowed to bring a makeshift one in the hallways) are free. Everything else (whatever will be administered to you like IV, medicine, and even the syringe and cotton balls in some places) you first have to provide and therefore buy at a nearby pharmacy.

Public hospitals, especially those in the suburbs where I currently live, are notorious for not having the necessary machines and tests. In fact, it’s not uncommon to find a family member manually pumping a patient’s oxygen with their hands. Therefore, the hospital itself would most likely recommend that you move to a bigger hospital in the city, which would be far from where you and your family live. Or, you could transfer to a nearby private hospital.

Essentially, even if you had a thousand pesos, you’re still kind of f*cked.

Act II

Okay, back to me and my somewhat first-world problem now: I have scrapped this essay three times and have tried to ignore this persistent noise in my head nagging me to write about it. The reason, if I’m being completely honest, is that I don’t like writing about my beloved homeland. Shocking!! I know!! Where’s my Pinoy Pride and all that jazz?! Before you confiscate my Filipino card and my weak-ass maroon passport, I hope you hear my case.

First: When I write, I romanticize the hell out of things. It’s probably a way to cope, but that deep dive is reserved for my therapist. Unfortunately, the reality of living in the Philippines is hard to romanticize. Plus, I refuse to.

I realize I won’t be able to write this piece unless I lay it all bare to you, so that’s what I’m doing now. However, I hate that I don’t even come off as passionate, much less patriotic. Just part exasperated, part defeated, part sad. As you can see, I don’t even have the energy to sneak in my metaphors. Not a fan of this version of my writing or myself.

Second: I don’t feel qualified enough to write about Filipino culture and society. This is something I have grappled with all my life: not feeling Filipino enough. (Oh, boohoo, right? Don’t feel bad for me.) Despite the fact that I am, no doubt, a true blue—red, white, three stars, and a sun—Filipina, I somehow feel less.

(Okay, in the interest of full disclosure, I have about a quarter of Spanish blood, but who doesn’t?! Spain colonized us for literally 300 years. My point still stands; I have never had any other home other than the Pearl of the Orient, land of kwek-kwek and sinigang.)

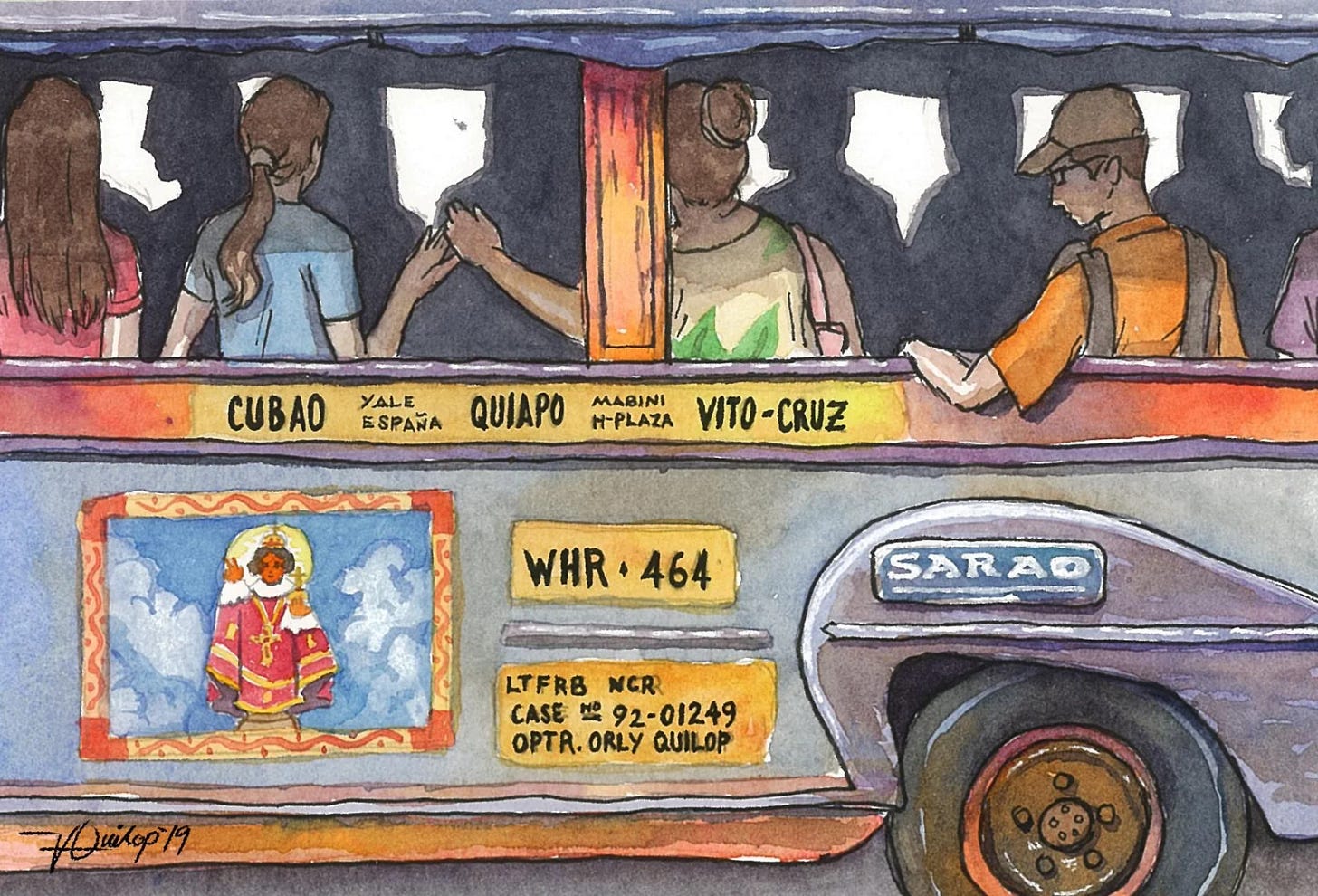

When this insecurity first took root is probably another topic reserved for therapy, but it’s definitely there. It’s evident in the way I envy my fellow kababayans who write in Tagalog or any other native dialect. When I attempt to do that, I immediately feel like an impostor because (and this is heartbreaking to admit) even my thoughts are in English. I also live in a middle-class suburban bubble. I work from home. My clients are from the West, and I have always worked for either Western companies or stakeholders. I rarely commute and instead book a Grab to and from wherever, or catch a ride with my friends. For more than half a decade, I lived in Metro Manila (Taguig, not Manila City, but still), and only rode the LRT twice, both times treating it like a happy excursion a tourist takes instead of the daily rush-hour chaos Manileño commuters have to endure.

In short, my family’s not rich at all, but I do enjoy quite a privileged life in a third-world developing country.

Act III

When I was in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital city, I was impressed by their walkable streets and organized public transport. How there are buses, bike racks, and trains for everyone. How there’s rarely litter on the streets.

I marveled at their easy access to third spaces, too. I went there during the summer, and after 5 o’clock, no matter if it’s a weekday, you’ll see people flocking to the city center, where there’s an abundance of shops, restaurants, and street performances. There are many museums and art galleries you can walk to. One I visited gave me a tour and didn’t even require payment—only donations if you were so inclined. And you’ll find a park with trees, benches, fountains, and playgrounds almost every three blocks. When I was there, I felt like work-life balance and a higher quality of life, regardless of how much was in my wallet, were more achievable.

It’s not the same here back home. Aside from the National Museum and Luneta Park, most decent museums, parks, and even libraries are in or around wealthier areas like Ayala, BGC, and Ortigas. If you don’t live in those areas, you’re probably not taking advantage of those spaces because you’re too busy commuting to get home. So really, only those who can afford to live in these neighborhoods have easy access to them.

The museums and libraries are rarely free. I just bought a pass for a museum located in Makati City, and it was 550 pesos, approximately 10 USD. For many Filipinos, that’s almost a full day’s wage.

So, where am I going with this? I guess what I’m trying to say is that I often feel stuck between my third-world reality and my first-world ideals. I imagine myself at the intersection, confused and brimming with guilt, looking left and right over and over until I’m dizzy. To my east, the developing; to my west, the developed.

It’s so hard to be full of pride when you’re also consistently disappointed. It’s hard to stay, no matter how deeply you love a place, when you know you deserve so much more, so much better. I want the access and opportunities that people in the first-world have, here at our streets. I want to be able to admit that out loud without sounding like a petulant spoiled brat. Because, maybe then, no Filipino would feel compelled to leave PH soil. Until then, I can’t blame anyone who does.

In one of her novels, Taylor Jenkins Reid wrote, “Don’t be so tied up trying to do the right thing when the smart thing is so painfully clear.” Sitting in the ER, thinking about the stark contrast between “developing” and “developed,” and whether Filipinos should choose to stay or leave, the smart thing was so painfully clear.

P.S. The Philippines is a huge part of my identity and current reality. So, it’s inevitable that it will come up in my writing. I know this essay feels like a bit of a downer (maybe I’ll be more cheerful next week!), but I must emphasize this is just one side of the truth. To share my full reality with you, I have to write about the good too. And trust me, there is plenty of good here at home. The Philippines isn’t just grime; it’s also glory. I aim to write about the latter (even though I don’t feel qualified or skilled enough to do so) hopefully soon.

PPS. To the insect that bit me, I hope you know I’m out for revenge.

Please don’t apologize for writing a “downer.” We feel how we feel.

thank you for this essay! i sometimes wish our country is easy to love. being an activist all throughout my college years literally woke my insides but mostly my soul about the situation of our fellow filipinos and the marginalized sectors. now that i’m in the world of adulting, i’ve realized that love is not enough and that there is serious accountability to be demanded to the government. then again, the fight goes a long way.

it’s hard to stay especially when you know as a human being that you deserve more than what this country gives you.